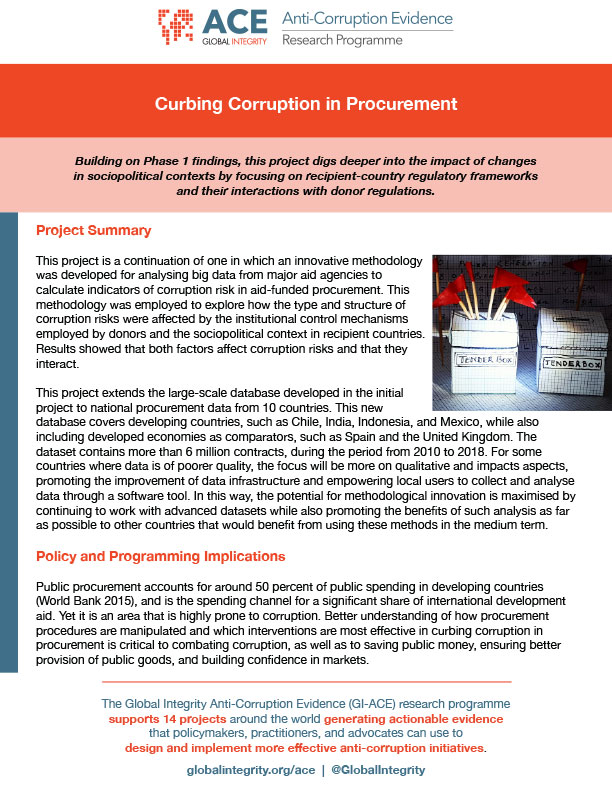

Building on Phase 1 findings, this project digs deeper into the impact of changes in sociopolitical contexts by focusing on recipient-country regulatory frameworks and their interactions with donor regulations.

Click here for the Project One-Pager

To learn more about this project, contact Principal Investigator Liz Dávid-Barrett.

Project Summary

This project is a continuation of one in which an innovative methodology was developed for analysing big data from major aid agencies to calculate indicators of corruption risk in aid-funded procurement. This methodology was employed to explore how the type and structure of corruption risks were affected by the institutional control mechanisms employed by donors and the sociopolitical context in recipient countries. Results showed that both factors affect corruption risks and that they interact.

This project extends the large-scale database developed in the initial project to national procurement data from 10 countries. This new database covers developing countries, such as Chile, India, Indonesia, and Mexico, while also including developed economies as comparators, such as Spain and the United Kingdom. The dataset contains more than 6 million contracts, during the period from 2010 to 2018. For some countries where data is of poorer quality, the focus will be more on qualitative and impacts aspects, promoting the improvement of data infrastructure and empowering local users to collect and analyse data through a software tool. In this way, the potential for methodological innovation is maximised by continuing to work with advanced datasets while also promoting the benefits of such analysis as far as possible to other countries that would benefit from using these methods in the medium term.

Policy and Programming Implications

Public procurement accounts for around 50 percent of public spending in developing countries (World Bank 2015), and is the spending channel for a significant share of international development aid. Yet it is an area that is highly prone to corruption. Better understanding of how procurement procedures are manipulated and which interventions are most effective in curbing corruption in procurement is critical to combating corruption, as well as to saving public money, ensuring better provision of public goods, and building confidence in markets.

Research Questions

- What is the impact of changes in recipient country interventions on corruption risks in aid, as well as national procurement spending?

- Are there displacement effects of donor anti-corruption policies, i.e., does improving controls in one area prompt corrupt actors to shift corruption to other areas with weaker controls?

Methodology

This project takes a two-tiered approach to extending the existing database:

- Full quantitative analysis for 10 countries with sufficient-quality data; and

- Qualitative and impacts approach where data is poorer quality.

A user-friendly interface for analysing the freely available data resulting from this project will be rolled out to a wide range of users, including in-country civil society activists, law enforcement officials, and anticorruption agencies.

Research Team Members

- Liz Dávid-Barrett, Professor, University of Sussex; Director of the Centre for the Study of Corruption

- Mihály Fazekas, Assistant Professor, Central European University; Scientific Director, Government Transparency Institute